Early humans scraped pictures onto cave walls with small sharp stones. Those marks illustrated their daily lives and history – their story. Over several millennia, those early cave drawings evolved into symbols, and in 600 BC, the Hebrew alphabet appeared. By the time of the ancient Greeks, Egyptians and Romans, there were written languages.

The Greeks wrote their words with a stylus, an instrument made of metal, ivory or bone. With this tool they were able to mark tablets coated with melted wax. Later, the Romans used vegetable dye inks with pens made from reeds. As an early form of the fountain pen, the dried reed was cut to a nib at one end and the hollow narrow stem would be filled with the ink. The scribe would press or squeeze the reed to force the ink out of the pointed end onto papyrus or parchment.

The first reference to the quill pen’s use came 1200 years later from St. Isidore, scholar and Archbishop of Seville, Spain, who died in 636 AD. He claimed the quill pen was in use 100 years earlier. It is believed the reed pen and the quill pen were used in conjunction – the reed pen for writing large letters and capitals and the quill for finer or small letters.

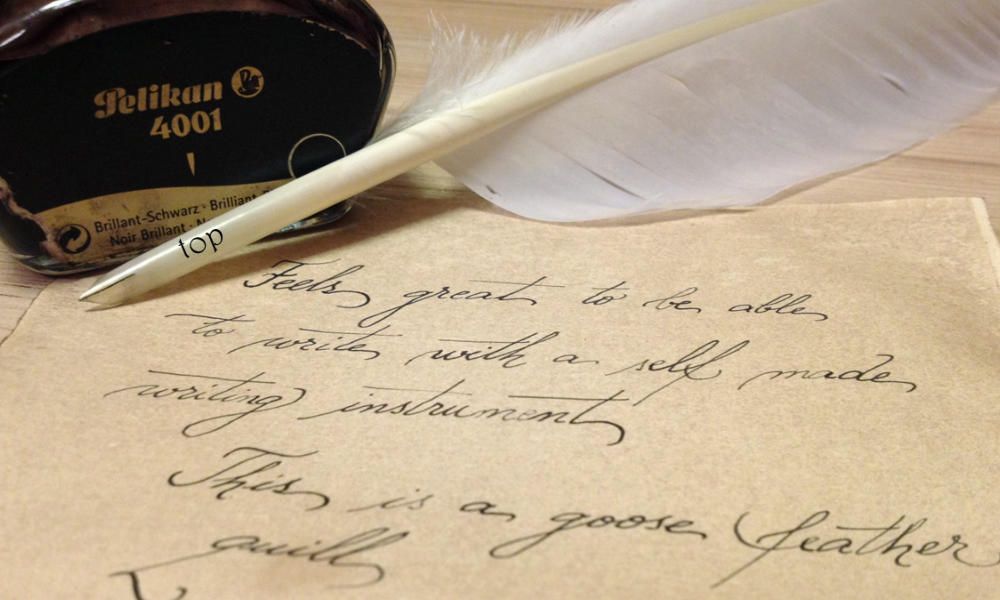

The quill pen became the writing tool of choice for the next millennium. It was made with a feather from the wing of bird. Goose feathers were most commonly used and the left wing was preferable. Most people, being right-handed, found it more comfortable when the feather curved away from the writing hand. Crow feathers were often used for finer lines.

At one time there was a shortage of geese in England. To support the demand for quills, they had to be imported from Europe. Russia exported millions of quills into England. Goose husbandry became an industry not just for sustenance, but for the quills. Each goose could supply wing feathers three to four times per year. It was sustainable income.

To take the goose feather from quill to pen took some effort before dipping the finished product into ink. First, the feather had to be softened in hot water. Otherwise, it could shatter when cut. The end had to be shaped and sharpened with a “pen-knife.” Once the tip was removed, the membrane within would be gently scraped away. Cuts were made at angles to form a point and a small slit was made at the nib, a design similar to the nibs of modern-day fountain pens. It was a skill and the quill pens didn’t last very long – a week at best if used daily.

The scribe could only manage to write two or three words at a time before dipping the quill into the ink again. Writing a document or manuscript was a long process and done with a practised hand. The writer used a soft touch when using the quill pen, to avoid bending it and losing blobs of ink to the paper. Old documents written during the age of the quill show ink spots and differences in the widths of the lines. It wasn’t a perfect writing instrument. There were smears and splatters and a reason for innovation.

The first steel pens were made by Wise in London in 1803, but they were not widely used as they, too, could be very messy. In previous centuries, there were other attempts at re-inventing the quill, but the innovations didn’t catch on. The Wise pen was the true beginning of the fountain pen.

In 1850, the fountain pen’s function had improved substantially. The quill gave way and with it went the romance of putting ink to paper. There is a romance in the history of the quill. It was used to scribe so many documents of note that still have meaning today. The words were important, but so was the quill – the instrument that gave us those words, as much a part of history as the Magna Carta.

“…though thou write with a goose-pen, no matter.”

William Shakespeare